News

Introducing Eileen Bird Kngwarreye

Today, I'd like to introduce you to Eileen Bird Kngwarreye (pronounced Ung-wahr-ay).

Eileen is an Eastern Arrernte woman, and her country is Arnumarra, near Gem Tree northeast of Alice Springs in Central Australia. Her family grew up at Harts Range where her brothers and sisters continue to live. Eileen grew up on her country at Harts Range but moved to southern Utopia to marry her husband, the late Paddy Bird. Together, they had eleven children (Maggie, Tanya and Alvira Bird among them). Paddy's mother was a renowned artist named Ada Bird Petyarre, sister to the famous Gloria and Kathleen Petyarre.

Her artworks mainly depict either the ʻArlatyeyʼ story or Women's ceremony. ʻArlatyeyʼ is the Anmatyerre word for Pencil Yam. Many female artists often paint dreamings associated with bush foods, as they are vital to Aboriginal traditional life. Through painting, they pay homage and celebration of the continued growth of these plants to flourish from season to season.

Eileen has been painting professionally since the mid 1990’s and her beautiful colourful works have a strong following.

The Anaty or Desert Yam

The Anaty (desert yam or bush potato) is a staple food for the Aboriginal people of Utopia. They are tubers, or swollen roots, of the Ipomoea costata, a fast-growing creeper with large purplish-pink trumpet flowers. It is usually found in the Acacia scrub lands and the yams grow underground with its shrub growing above ground, up to 1 metre high.

The anaty can be harvested at any time of the year and can sometimes be hard to locate as it can be growing as deep as 90cm underground. It tastes much like a common sweet potato and it is usually cooked by placing hot coals over it for about 20 minutes. It is then peeled before being eaten.

The Anaty is a central part of the Utopia Aboriginal people's dreaming and artists who have had this story passed down to them through their family lines can depict this story in their art. Examples of artists who paint this story include Jeannie Mills Pwerle, Lisa Mills Pwerle and Shakira Petrick Mills.

Cross-hatching or Rarrk painting

Cross-hatching, is a style that has been used in art making for many years by many civilisations. Its most common application in art making is in drawing where the artist wishes to 'fill' or shade a part of the artwork. Hatching is generally made by close parallel lines executed in drawing materials such as ink, pencil, charcoal, crayon, paint and the like, whereas cross-hatching is what it sounds like; another hatching pattern crossing the first one.

In Australian Aboriginal Art, the fine technique of cross-hatching (or 'Rarrk') has taken on a more structured and stylised appearance, and can have significant meaning when it is used in an artwork. It is used largely by the artists of the Northern Territory, and particularly in Arnhem Land in their bark or other fine work paintings.

The usual way Aboriginal artists achieve this is to pull a few strands of long human hair, hold them together at one end, dip them deep in the paint and then use the length of paint coated hair as a brush. The hair length is carefully pulled in a straight line across the surface of the artwork. The hairs, already straight with the weight of the paint, take the least line of resistance and straighten out perfectly, producing a fine, straight line. The process is repeated at regular intervals and then when this is dry, the same is done in the other direction. Aboriginal artists believe that these overlaid patterns of colour and line contain the power associated with that particular painting or story subject.

To view artists' work that we have in this style (click on the links below)

Eddie Blitner, Christine Burarrwanga, Reggie Sultan Apengarte

What is the Dreamtime?

The Dreamtime or Dreaming for Australian Indigenous people refers to the time when the Ancestral Spirits moved across the land and created life and significant geographic formations and sites.

Aboriginal people tell Dreaming stories to pass on important knowledge, cultural values, belief systems and law to later generations. These stories are passed on through a number of different ways – Ceremonial body painting, song and dance being the most common. By maintaining a link with the Dreamtime and Dreaming stories of the past to the present, a rich cultural heritage is created.

In many of the Dreaming stories, the Ancestral Spirits came to earth in human form and as they moved through the land, they created the animals, plants, rocks, rivers, mountains and all other formations and beings that we know today. These Ancestral Spirits also formed the relationships between Aboriginal people, the land and all living beings.

Once the Ancestral Spirits had created the world, they transformed into trees, stars, rocks, watering holes and other land formations or objects. These are recognised today as the sacred places and sites of Aboriginal culture.

Dreamings allow Aboriginal people to understand their place in traditional society and nature, and connects their spiritual world of the past with the present and the future.

Australian Indigenous Bush Foods

Bush tucker, or bush food, is any food that is native to Australia. Australian Aboriginals have used the environment around them for generations, living off a diet that is high in protein, fibre, and micro nutrients, and low in sugars. Much of the bush tucker eaten then is still available and eaten today.

There are many different types of Bush Tucker foods:

- nuts and seeds (eg. Acacia, Macadamia, Bunya nuts)

- flavourings and native spices (eg. bush pepper, lemon myrtle)

- berries (eg. Astroloma, some Solanum species)

- fruits (eg. Quandong, Ficus macrophylla, Syzygium, bush plum or Anwekety*)

- vegetables (eg. bush potatoes, yams, tomatoes)

- wattle seeds ground to produce "flour"

- drinks (eg. hot teas, infusions of nectar laden flowers, fruit juices)

- plant roots ground to produce a paste or flour (eg. pencil yams or Arlatyey*)

*This name comes from the Anmatyerre language (names may vary for other languages)

Many female artists often paint Dreamings associated with bush foods. This is because bush foods are vital to Aboriginal people living a traditional life. Through painting these bush foods, it is a celebration of the growth of these plants to flourish from season to season.

There are many Australian plants that are edible; and even some that are in very high demand as foods throughout the world. The only food plant well established as a large commercial scale crop, which is native to Australia is the Macadamia.

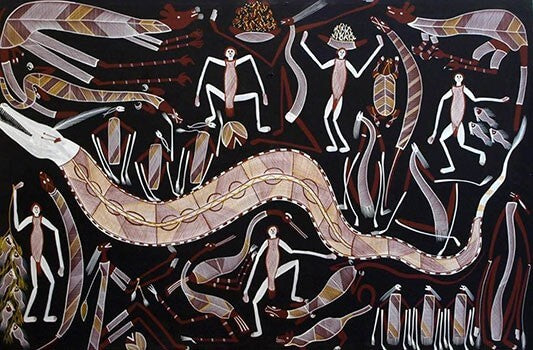

Introducing Gloria Petyarre

Gloria Petyarre was born near Atnangkere Soakage in 1945. She lived a very traditional lifestyle as a child, before moving to one of the established settlements in Utopia, NT.

Gloria, her family members and her skin family, first became interested in art making by participating in the Utopia Women's Batik Group introduced in 1977 and initiated by the Central Australian Aboriginal Media Association. With up to 80 members at a time, the Batik and Tie-die project became the seeding inspiration for the artists, and its tremendous success both in Australia and overseas led to another successful project introduced in 1988, again by CAAMA. This time, the artists were to paint on primed, stretched canvas finding it more exciting to work with than the silk and batik techniques they had previously used.

She merged traditional iconography and onto the new medium of silk and in doing so created a new art style. Gloria is a very dynamic and innovative artist and this has placed her in a unique position within the Contemporary Aboriginal art movement.

Throughout her career Gloria has been an ambassador for the art of her region and in 1999 Gloria won the prestigious Wynne Landscape Prize, which reaffirmed her position as one of the most talented and renowned contemporary Aboriginal artists.

The main Dreaming she paints is the ‘Bush Medicine Leaves’. The Bush Medicine Plant/Leaves refers to a species of acacia, which is used as part of traditional indigenous healing. Women collect leaves from this plant and boil them to extract the resin. The resin is then mixed with kangaroo fat, which results in a paste. This paste is used to heal bites, wounds, cuts and rashes and can also be used as an insect repellent. The leaves from the plant can also be brewed to make tea and can be used to alleviate symptoms of the common flu.

Gloria paints the leaves of the acacia plant, and her depiction of the ‘Bush Medicine Leaves’ has become iconic. Typically, she depicts the leaf of the plant in an upward movement. She will either paint a delicate, fine leaf or more recently she has been developing her style and paints a bolder, larger sized leaf.

Another important Dreaming story, which Gloria depicts is 'Mountain Devil Lizard Dreaming'. The Mountain Devil Lizard is a small lizard found in the spinifex and sand plains of the desert. The Lizard is seen by Gloria, her family and her people as their spiritual Ancestor. The Mountain Devil Lizard is what created Gloria's Dreamtime stories - she has said “Little lizard put the stories for we mob - for man and woman”. Gloria and her sisters are the custodians of this Dreaming and inherited the story of the Mountain Devil Lizard from their grandmother.

Gloria also paints the subject of ‘Awelye’, which is body painting for Women’s Ceremony. Awelye is derived from the traditional practice of Aboriginal women ‘painting up’ their bodies for Ceremony. These designs are painted onto the chest, breasts, arms and thighs.

COLLECTIONS:

Allen, Allen & Hemsley

Art Bank Sydney

Art Gallery of New South Wales

Art Gallery of Western Australia

Australian National Gallery

Baker-McKenzie

Campbelltown City Art Gallery

Flinders University, South Australia

Gold Coast City Art Gallery

Griffith University Collection

Holmes a Court Collection

Kerry Stokes Collection

Mornington Peninsula Regional Gallery

Museum of Victoria, Melbourne

National Gallery of Victoria

Powerhouse Museum, Sydney

Queensland Art Gallery

Queensland University of Technology

Riddoch Art Gallery, S.A.

Supreme Court, Brisbane

The Robert Holmes a Court Collection

University of New South Wales

Wadsworth Atheneum, Hartford, U.S.A.

Westpac, New York

James D. Wolfensohn Collection

Woollongong City Art Gallery

Woollongong University Collection

Macquarie Bank

University of the Sunshine Coast, Queensland

Singapore Art Museum

Museums and Art Galleries of the Northern Territory

British Museum

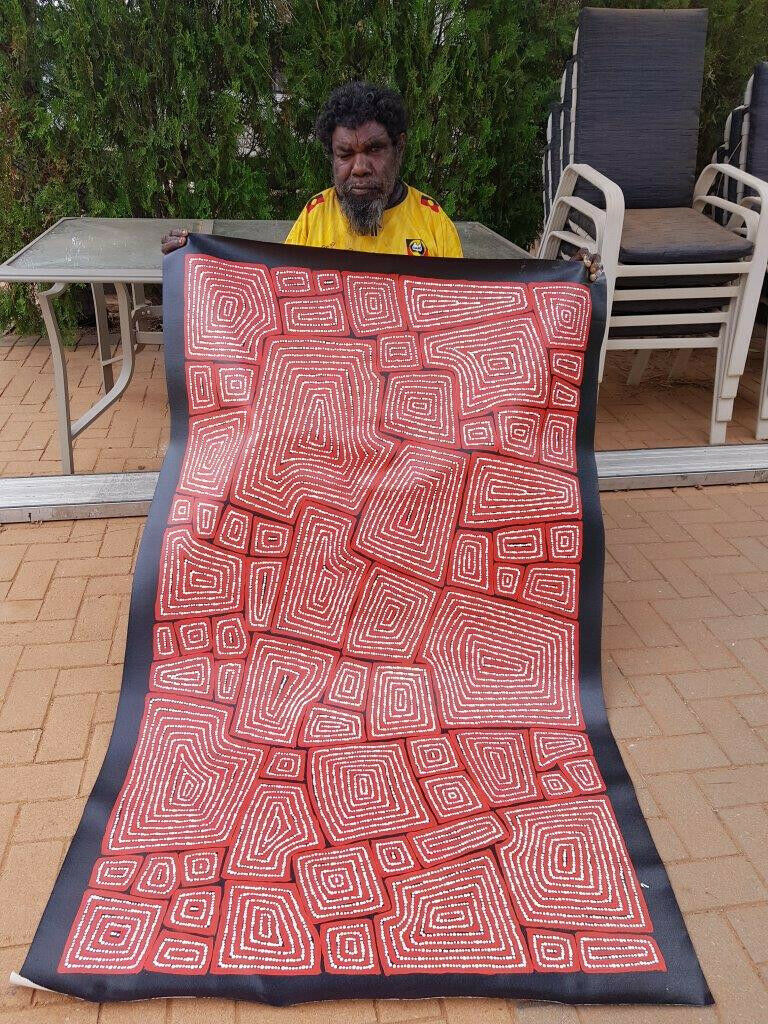

Introducing Thomas Tjapaltjarri

Thomas Tjapaltjarri was born sometime around 1964 in the Gibson Desert, Western Australia. Thomas and his family which includes fellow artists Warlimpirrnga, Walala, Yukultji, Yalti and Tjakaria led a completely nomadic life until they emerged from the desert, coming to Kiwirrkurra in 1984.

Dubbed "the Last Nomads" or "the Pintupi nine", they had had no contact with Western society until this point. Amazingly, he transitioned from an utterly traditional lifestyle to commencing as an artist within a matter of a few years and painting the traditional stories of his people.

Thomas paints simple, geometric designs and uses a dotting technique shared with other Pintupi artists such as his brothers, Warlimpirrnga and Walala, and with Willy and George Ward Tjungurrayi.

Thomas's works explore the stories of the Tingari cycle, a series of sacred and mythological songs connected to his birth ground. His Tingari Cycle paintings are associated with the artist's Dreaming sites located throughout the vast sandhill country of the Western Australian desert. Tingari are the legendary beings of the Pintupi people that travelled the desert performing rituals, teaching law, creating landforms and shaping what would become ceremonial sites. As far as we can know, the meanings behind Tingari paintings are multi-layered, however, the meanings are not available to the uninitiated.

It was at Kiwirrkuru that Thomas began to paint on canvas, setting down the stories and images of an unbroken cultural tradition stretching back tens of thousands of years. His style is strongly gestural and boldly graphic, one that is generally highlighted by a series of rectangles set against a monochrome background.

Thomas' paintings are exhibited widely in almost all aboriginal galleries in Australia and collected the world over.

Introducing Polly Ngale

Polly Ngale is one of the most senior custodians of her country Arlparra (or Ahalpere), in the heart of Utopia, located in the north west corner of the Simpson desert and roughly 350km north east of Alice Springs, along the Sandover Highway.

Polly belongs to the oldest living generation of Utopia women and her artistic career began in the late 1970s when she, like many of the women in Utopia, began working with silk batik before venturing into works on canvas.

She is considered one of the most accomplished painters from the Utopia region and is inspired by the Arnwetky (conkerberry) - a green tangled, spiny shrub that produces fragrant white flowers. After the summer rains tiny green berries begin to grow and ripen, changing colour over the weeks from light green to pinks and browns to yellow, to shades of red and purple when they finally ripen. The fruits very much resemble a plum and is often referred to in English by Polly as a 'bush plum'. The Arnwetky is a popular variety of bush tucker for the people of Utopia, as well as possessing medicinal properties.

During the Dreamtime, winds came from all directions, carrying the Arnwetky seed all over Polly's ancestors' Anmatyerre land. To ensure the continued fruiting of the Arnwetky, the Anmatyerre people pay homage to the spirit of the bush plum by recreating it in their ceremonies through song and dance, and in recent years, through painting. The patterns in the paintings can represent the fruit of the plant, its leaves and flowers, and also the body paint designs that are associated with it during ceremony.

For Anmatyerre women, the bush plum is a source of physical and spiritual sustenance - reminding them of the sacredness of Ahalpere country. Its story is crucial to Anmatyerre women's ceremonies.

Polly’s depictions of Arnwetky are the accumulation of a lifetime's knowledge about the country that she loves and feels a personal responsibility to care for. The power of the art resonates across geographical, botanical and spiritual dimensions.

Polly shares this country and the Bush Plum (Arnwetky) Dreaming with her sisters Kathleen Ngale and Angeline Pwerle Ngale. Like Kathleen, Polly creates her paintings by building up layer upon layer of colour to create multi-dimensional images. The two have often collaborated and painted together.

Polly's paintings are borne from traditional knowledge and her confident approach to painting can be seen in the way she assembles streams of seeds, piling dots upon each other to create rich thick fields employing glowing palettes of colour. Polly's works range from extremely fine dotting techniques with either interspersed colours or areas of varying colours and depth all blending together across the canvas. Through extensive over-dotting, she builds up layers of colour, blending or separate, to give a wealth of different and very attractive paint effects.

Since 1999, Polly's work has been exhibited extensively both in Australia and overseas and in recent years. Her work has appeared in the Telstra National Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Award since 2003. Her honourable mention as a 2004 finalist was followed by representation at the Contemporary Art Fair in Paris at the Grand Palais Champs Elysees. Polly was also represented in the exhibition Emily Kngwarreye and her Legacy at the Hillside Forum Daikanyama Tokyo in 2008.

What is a Skin Name or Kin Name

Many Aboriginal people have a skin name. Skin Name is an Aboriginal-English term derived from the English term 'Kin Names'. A skin name is a name given to an Aboriginal person at birth based on the combined skin names of their parents, or given by their community. A skin name is not a surname or last name.

Skin names are an important aspect of Aboriginal culture as it governs an individual's right to own certain Dreamings, as well as define their relationships and connections to traditional land and extended family.

| Western Desert Language Groups | Utopian Language Groups | ||||

| Warlpiri | Pintupi/Luritja | Arrente | Alyawarre | Anmatyerre | |

|

M F |

Jungarrayi Nungarrayi |

Tjungarrayi Nungarrayi |

Kngwarreye

|

Kngwarrey

|

Kngwarreye or Ngwarai |

|

M F |

Japanangka Napanangka |

Tjapanangka Napanangka |

Penangke

|

Penangke

|

|

|

M F |

Japaljarri Napaljarri |

Tjapaltjarri Napaltjarri |

Peltharre | Apetyarr | Petyarre or Pitjara |

|

M F |

Japangardi Napangardi |

Tjapangati Napangati |

Pengarte | Pengarte | |

|

M F |

Jupurrula Napurrula |

Tjupurrula Napurrula |

Perrurle | Apwerl | Pwerle or Pula |

|

M F |

Jangala Nangala |

Tjangala Nangala |

Angale | Ngale or Ngala | |

|

M F |

Jakamarra Nakamarra |

Tjakamarra Nakamarra |

Kemarre | Akemarr | Kemarre |

|

M F |

Jampijinpa Nampijinpa |

Tjampitjinpa Nampitjinpa |

Ampetyane | Mpetyane or Mbitjana |

Often people in the same language group refer to each other as 'brother', 'sister','aunty' or 'uncle' etc. This does not mean they are biologically related, but refers to their relationship to each other as set out by their Skin Name. If two women have the same Skin Name they might refer to each other as 'sister'.

Skin Names are spelt differently across different languages and dialects, for example Petyarre and Pitjara are the same name. These variations in spelling are a result of the process of writing and recording languages that were traditionally only spoken languages.

Traditionally, these kinship systems governed all social interactions including marriage.

Indigenous Art or Aboriginal Art?

The words ‘Aboriginal’ and ‘Indigenous’ are both used in Australia to describe the original inhabitants of the Australian continent. The word ‘Aboriginal’ is the established way to describe the first inhabitants, regularly used in contexts of Aboriginal community, Aboriginal health, Aboriginal art etc. ‘Aboriginal’ is also used as a noun, so a person is an Aboriginal as well as an Aborigine, which seems to be used less often in the media.

As the term ‘Aboriginal’ is the established way to describe first inhabitants in Australia, we then extend that to ‘Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islanders’ to cover all first inhabitants on Australia and its northern islands. Maybe the use of ‘Indigenous’ has come into use as a term to cover all these groups, and ‘Indigenous Art’ has perhaps come into use with it. It is certainly a term that we associate with use in North America, where we hear of the first inhabitants of Canada and USA described as ‘Indigenous Nations’.

But it seems that there are political aspects to the use of the word ‘Indigenous’ in Australia, as governments have incorporated the word into government department names and into policies. Zoltan Kovacs writes on language use in his Opinions column in the West Australian. In his article ‘In the beginning there were…Aboriginals’ in the West Australian on 25-26 January 2014, Zoltan Kovacs writes –

“The word ‘Indigenous’- written with a capital first letter and used as a substitute for ‘Aboriginal’ – has gained mysterious prominence in everyday language over the past 10 years or so. It is hard to see what benefit people who prefer it to Aboriginal find in its use.

Indeed it has the disadvantage of being essentially an adjective, though the Macquarie Dictionary surprisingly lists its use as a noun with the definition of ‘an Aboriginal or Torres Strait Islander’. It seems impossible to use it as a noun without doing violence to the language… Further ‘Indigenous’ has no plural, which is a severe impediment to its use as a noun.

On the other hand, the use of ‘Aboriginal’ as both adjective and noun and in the singular and plural forms has been well established for generations. Of course if there were evidence of a preference by Aboriginal communities for the use of Indigenous, then that should be a powerful argument in its favour. The evidence is to the contrary.

The State Government changed the name of the Department of Indigenous Affairs to the Department of Aboriginal Affairs last year as a result of what it said were the requests of the WA Aboriginal community and consultations with Aboriginal people. The change was made without evident dissent.

A WA Aboriginal leader of accomplishment, Robert Isaacs, has taken the matter further by telling Prime Minister Tony Abbott that many Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people object to the collective description of them as Indigenous. He wrote to Mr Abbott that he, ”as an Aboriginal person and Noongar Elder”, supported their objection to the term, which was increasingly used by government agencies. He argued, in essence, that the term robbed Aboriginal people of their identity.

A reasonable conclusion to be drawn from his letter is that Aboriginal communities are entitled to a sense of grievance if the decision to identify them officially as Indigenous was made without their views being sought and considered. Further it is undeniable that Indigenous is a neutral, bland word without traditional associations…it fails to capture and reflect the unique standing of an ancient people who were the first occupants and custodians of this land.

The word Aboriginal symbolically conveys this history and tradition and can be used respectfully. It is a name by which descendants of the first people of this country are known worldwide. After all, it is made up mostly of the word original.”

In a nutshell, the term ‘Aboriginal’ is so closely associated with Australian first inhabitants that it will remain the principal descriptor for all things associated with Australian Aborigines.